30

LIVING

Look back in hanger?

Insulin - the first 100 years. Until the discovery and

refinement of this life-saving, life-changing hormone,

anyone with "sweet urine disease" slowly withered

away. Medical journalist and health writer Susannah

Hickling takes a look at what happened in Canada in

January 1922.

Hangry is a term some people use about the

'feed me!' response to having a low blood sugar;

hypos make you hungry, and you can be quite

angry about it too. But until a momentous

day 100 years ago no one with diabetes ever got hangry

because of too much insulin - they just died.

Then one January day in 1922 the world changed

for people with diabetes. Fourteen-year-old Leonard

Thompson, emaciated and close to death when his father

brought him into Toronto General Hospital, Canada,

became the first human being to receive a shot of insulin.

In spite of an initial nasty allergic reaction at the site

of the injection from an extract derived from mashed-up

cow pancreas, his blood glucose levels dropped. By the

time he received a second shot two weeks later, scientists

had worked hard to remove impurities in the raw

pancreas extract. Not only was there no recurrence of the

abscesses, but there was a remarkable improvement in

Leonard's health. He continued taking insulin and went on

to live a further 13 years, dying of pneumonia at the age

of 26.

Previously, a diagnosis of Type 1 diabetes was a

death sentence. It was far from being a new condition

- diabetes was first described in ancient Egyptian

manuscripts dating to around 1500 BC - but no one knew

what caused it or how to treat it. As late as the beginning

of the twentieth century in pre-insulin days, doctors

were prescribing a starvation diet, so if the diabetic

ketoacidosis (DKA) didn't get you, the lack of food would.

Once diagnosed, people were lucky if they lived more

than a few months.

In 1889, Strasbourg physicians Joseph von Mering and

Oskar Minkowski localised the cause as being linked to

the pancreas - a deduction made on the basis of dogs

becoming sick and dying after this organ was removed -

and then in 1910, British physiologist Sir Edward Albert

Sharpey-Schafer realised that one key chemical was

absent from the pancreas of people with diabetes. He

called this missing chemical "insulin", after the Latin word

for island, "insula", in reference to the island-like clusters

of cells in the pancreas, the islets of Langerhans, which

produced it. These had been discovered by a medical

student of the same name in 1869.

No man is an island

Scientists worked out that these cells were destroyed

in Type 1 diabetes. It was also theorised that insulin

controlled the metabolism of blood glucose, and that a

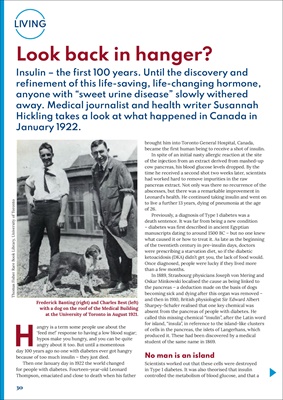

Banting, Best and dog.